THE CLYDEBANK BLITZ

At 6am the following morning the population emerged from shelters to a shattered and burning town.

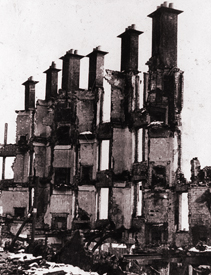

Clydebank burns, 13th of March 1941

THE CLYDEBANK BLITZ

At 6am the following morning the population emerged from shelters to a shattered and burning town.

Clydebank burns, 13th of March 1941

"I came into town to look for my family. Oh, what a nightmare! The place was smashed to bits, everything was burning. I had to climb over mountains of rubble to get to the street where my family lived. Our street was demolished and on fire, some houses were smoldering empty shells. I was sobbing uncontrollably, I couldn’t find anybody, it was the most terrible feeling I have ever had. I was only 17 and I felt like the only person left in the world".

"We lost everything, I had the clothes I stood in and a case with a Thermos flask. My father and I stood inside the shell of what used to be our building. It was just four burned walls. I looked up, all that was left was the grate and a pot with what was supposed to be our dinner. It may sound terrible, but I was glad in a way that my mother had died the year before, she loved that house, it was her life. It would have destroyed her to see it like that. I’ll never forget that burning smell till the day I die, it wasn’t the smell of death, it was the smell of everything”.

“All my family and relations stayed in what used to be called the Holy City, every single one of them lost everything they owned".

"We lost everything, it was raining incendiary bombs, I counted seven which had burnt out in my small back garden. They were all over the roads and gardens. Losing everything like that gave us a deep sense of value. We really appreciated what we had from then on”.

“When I came out of the shelter I remember thinking, what a mess , it was numbing. You just couldn’t take it all in, rubble, mountains of it, houses sliced open, walls all black and burned”.

“My mother took us to the rest centre in Radnor Street. We had lost everything, our house was a burned empty shell. There were lines of bodies along the street covered with sheets and lots of injured people. It’s strange the things you remember, there was a woman’s feet sticking out from under a tarpaulin, she still had her slippers on. My mother said, lets go, there are a lot worse off than us”.

"Walking through the devastation the next day, it was numbing,we were all struck dumb. My husband saw the parachute mine that hit the terraces in Second Avenue. It floated down over Third and Second Terrace and crashed into the back of First. There was a massive explosion. They were trying to take cover in plots about a quarter of a mile away and were blasted over a fence and up against a wall. The whole block of buildings were blasted across to the other side of the road. I saw it in the morning, it was horrific. You felt all these emotions at once and could hardly talk or even cry. It was a dreadful sight, there were people and little children torn apart, just like rag dolls, all over the road. 88 people were killed in that street”.

"Walking through the devastation the next day, it was numbing,we were all struck dumb. My husband saw the parachute mine that hit the terraces in Second Avenue. It floated down over Third and Second Terrace and crashed into the back of First. There was a massive explosion. They were trying to take cover in plots about a quarter of a mile away and were blasted over a fence and up against a wall. The whole block of buildings were blasted across to the other side of the road. I saw it in the morning, it was horrific. You felt all these emotions at once and could hardly talk or even cry. It was a dreadful sight, there were people and little children torn apart, just like rag dolls, all over the road. 88 people were killed in that street”.

“Through it all I only saw one incident of hysteria. A shelter at the High Park got hit. It was really bad, arms and legs sticking out of the mud. A lot of children got killed. Anyhow this woman was screaming, my sister, my sister, everyone else was so quiet”.

“My cousin went up to visit her friend in Napier Street. Two parachute mines had landed at the back of the houses. Her family went up to see if they could find her, they never found a trace of her body, all they found was one of her black patent shoes, then they knew she was dead”.

"A bomb had hit the tenements in Whitecrook Street, there were a lot of people killed and injured. My cousin was lifting a man into an ambulance who had lost his legs in the explosion. A bomb came down and exploded at the end of Stanford Street. The blast took his legs, they both bled to death”.

“It was a miracle that anybody survived in our shelter. We were on the edge of the crater and it seemed as if the shelters further away got the worst. The injuries were terrible, people were horribly burned and had lost legs and arms. Some were on fire from head to foot. These people were your neighbours, people you had known all your life".

“The dead were laid out in rows in the school. They were covered with sheets, hundreds of them, it was a dreadful sight. Watching all those people walking amongst them, trying to find their relatives, it broke your heart to see it, it’s a sight etched in my mind for ever. All those bodies lined up in neat rows, after all that noise it was the silence that got to you".

"There were not enough coffins, so the dead had to be buried wrapped in white sheets tied with string. There were hundreds of them laid out in the school hall, it was a pitiful sight".

The town was evacuated. 48,000 refugees were set adrift and spread afar, many never to return. That evening, Clydebank still burning, the bombers returned to a near deserted town to complete their task. When the drone of the last bomber had faded 528 lay dead and 617 had been seriously injured.

It had often been said that Clydebank Blitz was unsuccessful. The basic objective of 'Blitzkrieg' is to cause as much dislocation and social upheaval as possible and to strike terror into the hearts of the population. A massive housing loss suffered; 4,000 had been completely destroyed, 4,500 seriously damaged. In all only seven houses out of a total of 12,000 remained intact.

Many industrial targets received directs hits or severe blast damage and incendiary damage; Beardmores, The Royal Ordnance Factory, John Brown’s Shipyard, Arnott Young, Rothesay Dock, Tullis Engineering and Singers Factory, the massive Singer’s wood yard destroyed. Many large schools and churches perished. At one of the primary targets – the MOD oil storage at Dalnottar, on the periphery of the town – eleven huge tanks had been destroyed, others sever

ly damaged. Millions of gallons of fuel were lost in the resulting inferno. When the site was finally cleared, 96 bomb craters were counted .

ly damaged. Millions of gallons of fuel were lost in the resulting inferno. When the site was finally cleared, 96 bomb craters were counted .

There can be no doubt that the Blitzkrieg in Clydebank succeeded in causing massive dislocation and hardship to the population. But Clydebank people were no stranger to hardship, as those acquainted with the towns history will know. Importantly, the psychological effect was the exact opposite of what was intended. Rather than divide the community and throw it into frenzied panic, it strengthened and immeasurably hardened peoples’ resolve to survive and resist.

There was however a lingering anger, tinged with sadness. The once close-knit communities passionately desired to be reunited. This never happened. The ties severed, many thousands drifted; time passed and people began to make new lives else where. Many still bear the mental and physical scars; all have vivid recollections. The Blitzing of Clydebank was as far-reaching in time as it was in effect.

“It was terrible to see the town that you lived and grew up in disappear in two nights, they should have rebuilt the place to give the people a chance. They had paid dearly, they just bulldozed the rubble into heaps and hid it. It lay about for too long, it makes me angry when I think about it”.

“It was terrible to see the town that you lived and grew up in disappear in two nights, they should have rebuilt the place to give the people a chance. They had paid dearly, they just bulldozed the rubble into heaps and hid it. It lay about for too long, it makes me angry when I think about it”.

“It was far too long before they thought of starting to rebuild the town. It was too late, people had been moved elsewhere and had begun new lives. Years later I cried when they pulled down Singers Clock. You could see it from anywhere in Clydebank. I thought, oh, God! ...It was the only thing left, it came through the Blitz untouched. It was a symbol of survival and meant so much to the people of Clydebank, I hate them for that”.

Acknowledgments

The stories in these pages were selected from interviews of the following people.

Mr and Mrs Robert and Elizabeth Busby

Mr Edward Coyle and Mrs Frances Coyle

Mrs Margaret Graham

Mrs Flora Johnston

Mrs Effie Morrison

Mr and Mrs Bernard and Marjorie McCabe

Mrs Rachel McKendrick

Mr William Scott

Mr Bill Sharp

Mr and Mrs David and Jean Walker

Paintings

Tom McKendrick DA. RSW. RGI

Written and compiled by Tom McKendrick © 1986