IRON

Iron Exhibition Collins Gallery Strathclyde University

A superb show by Tom McKendrick

mourns, celebrates and explores

Glasgow's great shipbuilding past, by

lain Gale.

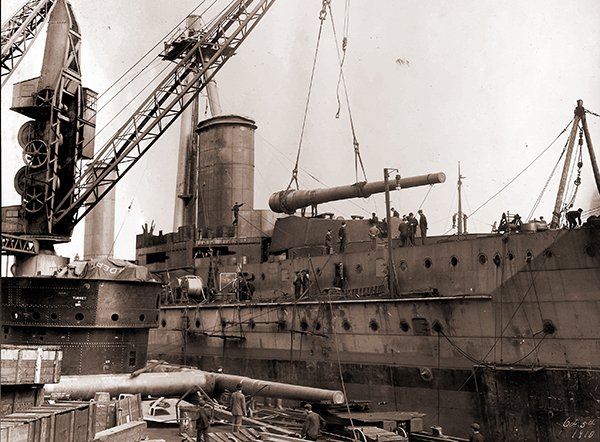

It was the lifeblood of a city. For century shipbuilding sustained Glasgow - fed it, clothed it, housed it, and in return Glasgow gave its men. Hundreds of thousands of them - to be sacrificed in the cathedrals of the Shipyards, to the gods of the battleship and liner

They made their libations in sweat. Their prayer books were the pay slip

and the time sheet; their litany the poetry of the imperial measurement.

Anyone who thinks this a somewhat fanciful rendition of an old and

well-worn story - the religious analogy a little precious - should

visit Iron, Tom McKendrick's extraordinary new display at Glasgow's

Collins Gallery.

Without

a hint of contrivance, McKendrick has transformed the exhibition

space

into a temple to the rivet gods of the Clyde. And he is well qualified

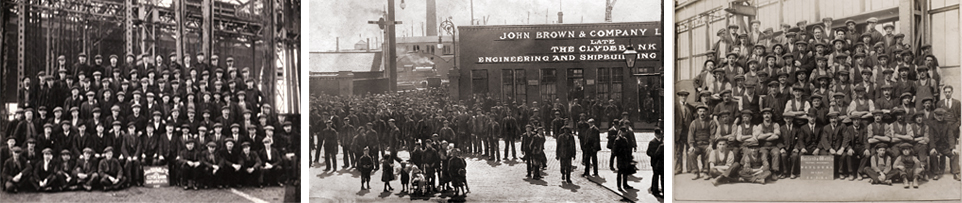

to do so. Born in Clydebank in 1948, McKendrick became an apprentice in

John Brown's shipyard at the age of 15. The tale he tells of the reality

of that existence is bound to strike home with his fellow ex-employees.

It may reduce some to tears. Even Hard Men sometimes cry.

![]()

![]()

To the doleful accompaniment of a soundtrack of hammer blows, accordions, Bagpipes and muttered oaths, especially composed by Alasdair Fleming, we enter. McKendrick's temple. Before us sits The Great Timekeeper - an endlessly ticking pendulum around which seven model dreadnoughts have been placed - perhaps in supplication. In the carefully engineered half light of the gallery the immediate-effect is overwhelmingly devotional. But resist the temptation to kneel.

Turn to the walls, around which the artist has are arranged his side chapels. Here are the altars of the Clydeside religion presented as archaeological artefact we are gazing on the vanished gods of a lost civilisation and the simile does not end there. McKendrick explains, Iron is fundamental to man's existence. God like it fell from the sky the product of a supernova to be discovered by man in the first Ion Age. But what we are looking at is Mckendrick homage to the people of the second Iron Age. Of course, it's not an entirely original idea. Returning to Glasgow in the 1940s, the colourist J D Ferguson saw the giant ships in religious terms. They were, he said cathedrals of the Clyde. Ferguson however, unlike McKendrick, never had the temerity to realise his vision.

![]()

![]()

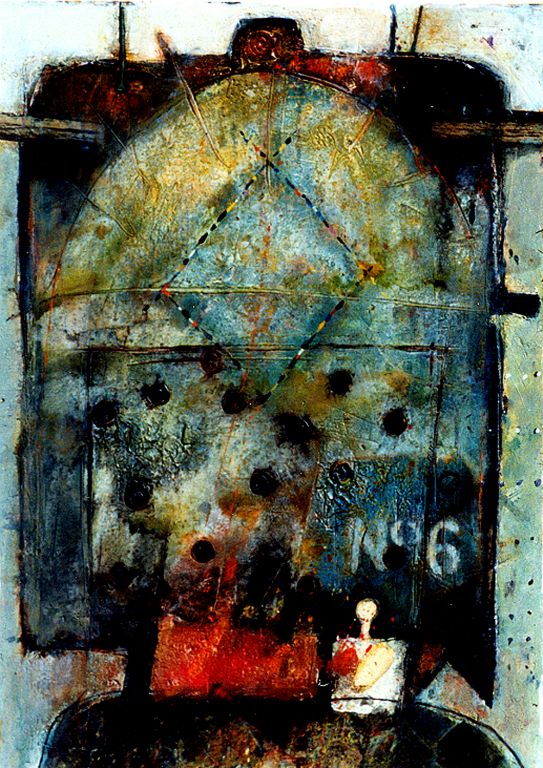

Three examples of exhibition paintings. Mixed media 55cm x 75cm

Like Ferguson before him he sees the heavy industry of the Clyde as the natural repository of the innate Ceilticism of the exiled Highlandman. In these powerful images of tribal faith, Ossian has been formed into a "patter-merchant" and then re-imagined in the visual language of another, simpler age. All this is captivating enough. But what lifts this exhibition above the ordinary, what gives it the power to be a landmark event in Glasgow's cultural history, is the secondary level onto which McKendrick now transports his audience. Interspersed around the walls, at intervals between and behind the altars, are paintings - richly encrusted, semi- abstract canvases which relate directly to the three-dimensional tableaux before them. Such is their power and presence that they would on their own have made an impressive and evocative shows.

Using,a heavy impasto in a palette Pre-dominantly blue and ochre, flecked with gold, bronze and red, McKendrick conjures votive images which evoke the spirit of Art Brut - the cathartic graffiti of Dubuffet and Burri. Closer to home, they also resemble the Bulkhead series of paintings created by John Kirk-wood in the 1980s. Like Kirkwood, McKendrick locates himself within a strong, indigenous artistic tradition of examining Scotland's industrial heritage.

Now, in the temporary cathedral of the Collins Gallery, McKendrick's altars

define the seven sects of the great religion. Totemic high priests jealously

guard not only the altars but also the skills of their own learning -

their trades - passed down as arcane wisdom through the generations. At

the Altar of the Sacred Hammer, 12 such guardians keep watch.

![]()

Spark and Hammer Altars

As McKendrick himself has explained, in the closed society of the shipyard, the workers created their own mythology in which demigods from the Gorbals perpetrated feats of Herculean proportions. Their legends were perpetuated by word of mouth in a storytelling tradition, which mimicked that of their ancestors. Mckendrick has made the equation that so many of his fellow shipbuilders were essentially- transplanted Highlanders.

If they have not already done so, Messrs Lally and Spalding should hurry along to the Collins Gallery, cheque book in hand, for if anything deserves to be in their new Gallery of Modern Art...it is IRON...in its entirety or at least in part.

"What we would like to see", wrote Ferguson in his 1943 book Modern Scottish Painting "is art in the same class as the Queen Elizabeth." Look no further.